Climbing in Lofoten’s Magic Islands

by Chris Vultaggio

Seven countries in as many weeks, and I can’t remember the last time I slept in my own bed. From the Welsh highlands to the shores of the French Rivera, Portugal’s rust-colored cities to the sleepy yet seductive Basque region, I’d trod my way through endless production days camera in hand.

I was dreaming of home, but I couldn’t turn away from the alpine siren song of summertime: that scorching time of year where the mountains beckon with cooler altitudes and crisp air. Plus, I had airmiles to burn and was itching for adventure beyond the crowded streets of Europe’s old world cities.

Places like the high Sierra, Chamonix, the Pacific Northwest, and even Scotland weighed in as travel contenders, but there was one place that always stood tall, dark, and mysterious in the back of my mind: Norway. Deterrents like challenging logistics and fickle weather, not to mention its reputation for being expensive, have kept me at bay for years, especially with no first-hand beta to draw upon. But as usual the internet went about its dirty business, and after one too many google searches on “Lofoten climbing” I got sucked into its lore of giant spires and Tolkien landscapes. Before long I punched “confirm” on airfare to a tiny airstrip in the Arctic Circle.

Aside from the legendary climbing and hiking, I would have the chance to field test some new Mountainsmith gear, including a brand-new version of my favorite ultralight daypack the Scream. Also on the test block were a shiny set of Halite 7075 trekking poles, and the 2018 women’s Tour lumbar pack.

_________________________________________________________________

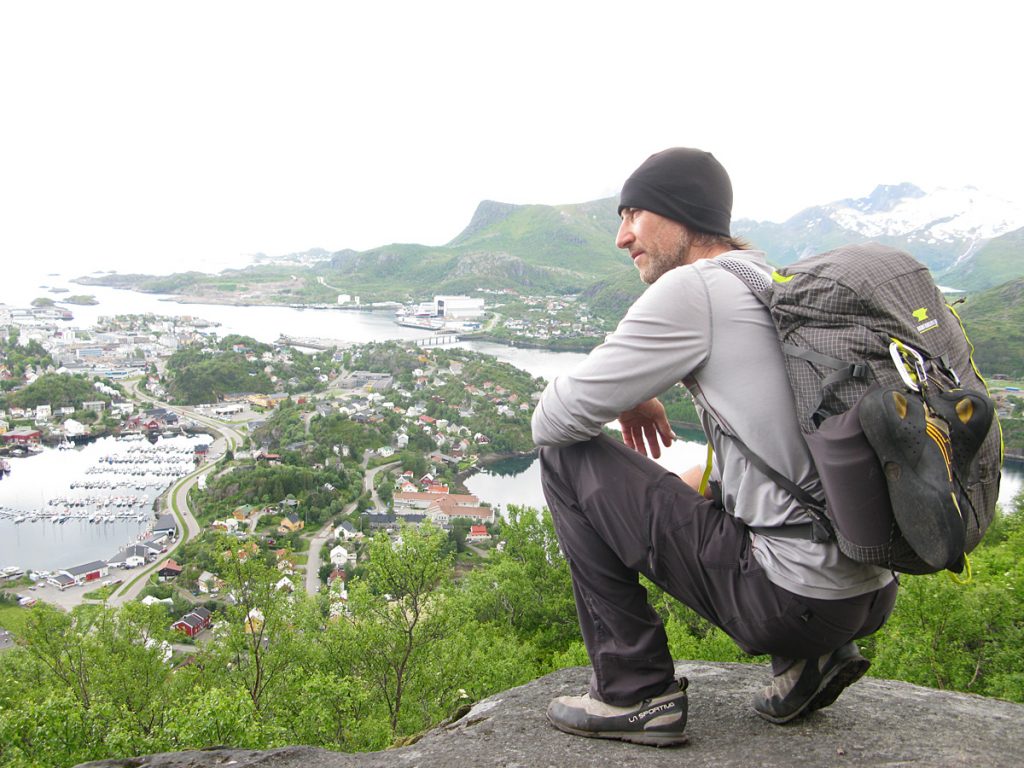

An archipelago off Norway’s coast, the Lofoten Islands are most often modified by the word “magic.” The landscape is a turquoise sea dotted by an infinite number of jagged peaks, intercut by winding rivers and fjords. Warm air from the Gulf Stream tempers the region, providing an unusually mild environment at such a high latitude (200km within the arctic circle). Months of 24-hour sunlight add to the playground feel, and the trinity of terrain, weather, and daylight make for an adventurer’s paradise. Surfing, hiking, mountain biking, trail-running, mountaineering, ice climbing, rock climbing, backcountry skiing, and kayaking are all world-class.

I hoped to sample as much adventuring as the weather would permit, but was focused on climbing – one route in particular. Like many who set out to climb in Lofoten, I was drawn in by the classic route Vestpillaren Direct (5.10d grade III-IV): 1300-ft of perfect sustained granite, towering above crystalline waters and touted as one of the best of its grade on the planet.

Before jumping on the Vestpillaren we warmed up with a few days of shorter routes, including a fantastic five-pitch 5.9 tower locally-known as the Goat. Lofoten’s rock is quite similar to the coarse-grained granite of Little Cottonwood Canyon in Utah, but with the pink color of Acadia National Park. When dry the stuff is like Velcro, and even when wet it’s climbable – which is good considering the local climate.

Lofoten is a trad climber’s dream with long uninterrupted cracks, corners, and flakes that stretch thousands of feet above the Norwegian Sea, well-protected and sustained. Much of the climbing is crack and slab, and I found endurance and technique more important than power. Trad ethics rule here as well – few fixed anchors mean true high-commitment adventure routes.

After the Goat I decided to make a play for Vestpillaren. Stable weather was on the horizon, and at 13 long pitches we knew we’d need a solid high pressure window to safely get up and off the pillar. With the midnight sun there wasn’t a concern for being benighted, although it felt wrong to leave the ground without a headlamp on such a long route.

My partner and I started the route just as it went into the sun, around 11am, fingers cold on the shaded granite. While notorious for being choked with climbers, we were the only ones at the base, with one party above us finishing the first pitch. We shadowed them for the first 500 feet, until they retreated from the top of the fourth pitch – the last place to easily return to the ground.

Success on long routes often depends on going light and fast, our pared-down kit consisted of exactly: the climbing rack, 70m lead rope, 70m tagline for retreat, 1L of water each, 3 energy bars each, a pack of cough drops to fight thirst, 1 lightweight down jacket each, our approach shoes, a camera, a roll of 1.5” tape (our first aid kit), and the Halite trekking poles for the descent. We weren’t the lightest, but we certainly packed light for such a long and committing route.

I wore the Scream pack from the start of the first pitch until we returned to the car over 16 hours later, including while onsighting sustained 5.10d terrain. Two features matter most in this type of environment: durability and weight. One often impacts the other, but in this case the Robic/Cordura fabric allows for an ultralight pack that stands up to the rigors of such a long route. Throughout the night I ground the pack into the coarse granite while climbing, used it as a cushion to rest at hanging belays, and essentially beat the crap out of it like some maladjusted gorilla with a piece of Samsonite luggage.

The pack looked not much worse for wear once we returned to the bottom, its bomber materials holding up nicely to my abuse. Which, along with my thirst, grew exponentially as we climbed into the next morning.

While the Scream line always fit well, I felt earlier versions sacrificed comfort for the featherweight metric. I could load up the lightweight pack and it’d stay put, but over a long day the straps would start biting into my shoulders. Not so with the 2018. Well-placed padding went a long way to keeping me comfortable, especially when the pack grew heavy on the four mile descent, where it was loaded with the two ropes and climbing gear – approx. 25lbs.

Accessing the bag’s compartments was easy, with an ample top compartment for bars and food, a secure bladder pouch, and stash pocket on the outside for my phone/climbing topo map.

We watched the sun trace a halo above, looking down upon tiny islands in the azure waters. Hours and pitches started to blend together, as we were alone on the wall through the night. Although sunlit, the road far below grew silent in the late hours as the light changed from overhead to low-angle. Sometime around 1am the walls faded from grey to a warm yellow, and shadows changed a familiar landscape into a different world.

No threat of darkness meant we weren’t in a hurry, and were able to take our time at belays to rest and scope the next pitch. With the greatest difficulties coming late in the climb we needed to dig deep, both physically and mentally. Climbing hard unfamiliar terrain at 4am, after more than 12 hours on the wall, was nothing I’d experienced before. But we finished in style, and at 530am we were on a panoramic summit sorting our gear.

I learned early in my climbing career that it’s the parking lot that’s celebrated, not the summit, and with a long and steep descent awaiting we decided to get moving. Drained, dehydrated, and hungry we were facing some steep fourth-class terrain to get down, some of which required careful downclimbing (or a rope) to avoid slipping and falling thousands of feet. In our tired states I was more nervous about un-roping to descend than the actual climbing.

At first I brought the Halite poles thinking we’d grab a few photos and maybe use them for comfort – turns out they saved our skins as the descent was so steep it’d require hand-over-hand climbing on the way up. The top ridge was mostly navigable, but at times it felt like low fifth class climbing, and the poles took a lot of stress out of an otherwise nerve-wracking descent.

Trekking poles are among the more unsung tools of the outdoors – they’re not exactly high-tech gadgets worthy of gear junkie lust. In the case of the Halites however, the fact that they collapse to a very compact 16” allowed me to carry they on the climb secured in my pack. Most poles collapse by telescoping, but the Halites separate like tent poles. This enables a smaller profile, and combined with the ultralight material, enabled me to carry them while climbing without noticing the weight. Which, after a 16-hour vertical ascent, is saying a ton.

On the way down they performed as expected – rock solid like any other Mountainsmith gear. Carbide tips were stable on talus, mud, scree, and stone. The cork grips were comfy, and wrist straps helped keep the poles in place.

Nearly 20 hours after starting our hike to the formation, we returned to our car, exhausted but fulfilled from the night’s adventure. Since those long days I’ve had the chance to return home, finally, and I’ve found myself looking forward to darkness, where I can return to the embrace of the night sky for the first time in weeks.

_________________________________________________________________

Often times I am asked why – why as climbers do we suffer, struggle, and willingly put ourselves in dangerous situations. My best answer is personal growth, coupled with the reward of the memories that can only happen in situations where you push yourself past comfort. I aspire to live a long life, and when it draws to a close I am hoping to revel in the reverie of a lifetime of memories made in wild places. Those memories are not free, and their cost is also their gain: heading into the unknown, staring down fear, and the desire to struggle on the path to experience.

Love this one!!